A GENEALOGICAL MISCELLANY, MADISON COUNTY, TENNESSEE

By Jonathan K. T. Smith

Copyright, Jonathan K. T. Smith, 1996

THE MADISON COUNTY POOR HOUSE

(Page 24)

All too often researchers are not aware of their varied ancestry; among their forebears may have been those who led such unfortunate lives that they lived a portion of their lives dependent upon others, as individuals and as institutions, to help them survive. In order to provide a background for some such persons in Madison County in former times the following article has been prepared.

I.

For many years it was an official practice for the county courts of Tennessee to pay individuals a stipend, usually on an annual basis, who were willing to offer "board and keep" for local indigents, persons "down on their luck," usually handicapped or too old and/or infirm to support themselves. This system of handling a serious social need must have known many abuses. There were persons willing to keep "paupers" just for the money they received for having done so, a practice leading to mistreatment to helpless individuals caught in the web of poverty. There were undoubtedly kind-hearted persons who did provide the indigents they kept with sufficient food, clothing and other care.

Later in the antebellum era state law required each county to provide "an asylum for the poor thereof, " the site and buildings constructed "solely with a view to promote and secure the health and comfort of the inmates." Each January, the county court appointed a three-member board known as "the Commissioners of the Poor" to serve for the ensuing year. They were to admit or reject persons to the asylum and appoint a superintendent with whom they managed the poor asylum. In order that orphan children or those youth whose

(Page 25)

parents could not support them would not become a burden to the county, in the asylum or otherwise, they courts were allowed to bind such unfortunates to persons as apprentices until age twenty-one if a male and age eighteen if a female.[1]

Early in the 1840, the county court of Madison County, composed of justices of the peace or magistrates who provided the basic government services for the county established a poor house. Indigents were kept on this tract and reports were made as to its operation.[2] In July 1848 the magistrates learned that the premises of the "poor house" were "in a delapidated condition and it further appears that said house and premises are of little or no use to said county," and a committee was chosen to dispose of it.[3]

On January 1, 1849, another committee was chosen from among the magistrates "to select a suitable site within four or five miles of Jackson, whereon to erect a poor house for Madison County" and it was empowered to contract for such land and have suitable buildings erected thereon.[4] This group bargained with Samuel Lancaster for a 100 acre tract, located about two miles north of today's courthouse, for $600, in the spring of 1849.[5] In January 1850, John Irvin was appointed treasurer of the poor house, a managerial post.[6] This farm was in operation until 1854 when it was disposed of as it had "not answered the object of its establishment."[7] It would be after the Civil War when another poor house was established and the old system of paying individuals to keep "paupers" was re-instituted until that time.

The antebellum efforts of the county court to provide permanent housing for indigents was doubtless well-intentioned but it is apparent from the records of the court that these efforts proved largely futile because of a lack of realistic management and under-funding.

References

1. CODE OF TENNESSEE, edited by Return J. Meigs and William F. Cooper. Nashville, 1858, volume 2, pages 341-345: Chapter One: Of Provision for the Poor, Articles I-IV.

2. Weston A. Goodspeed, HISTORY OF TEMNESSEE, Madison County volume. Nashville, 1887, page 806.

3. Madison County, Tenn. County Court Minute Book 4, page 360 (January 1845), page 554 (January 1847), page 696 (July 3, 1848).

4. IBID. Book 6, page 5.

5. IBID. page 37. Reported April 3, 1849. Deed Book 13, page 615. Officially purchased May 7, 1849 and registered July 18, 1850.

6. Madison County, Tenn. County Court Minute Book 6, page 101.

7. IBID. Book 7, page 297: July 3, 1854.

II.

Shortly after the Civil War there was a movement towards providing a better organized and less expensive manner of providing for indigents. The magistrates of the Madison County court appointed a committee on July 2, 1866 to "select a site for the erection of a 'Poor House' and its cost."[1] The court lagged in its commitment to provide a permanent institution to house "paupers"; over a period of four years other committees and individuals on the court were appointed to investigate the possibility of acquiring land for a "poor asylum."[2] Finally, in the fall of 1870 the court authorized a definite selection and purchase of a farm for a poor asylum.[3]

On January 2, 1871 the county magistrates approved the December 6, 1870 purchase of 257 acres and a small tract of 14 adjoining acres, added to provide a "straight" northern boundary for the farm; reportedly "very good

(Page 26)

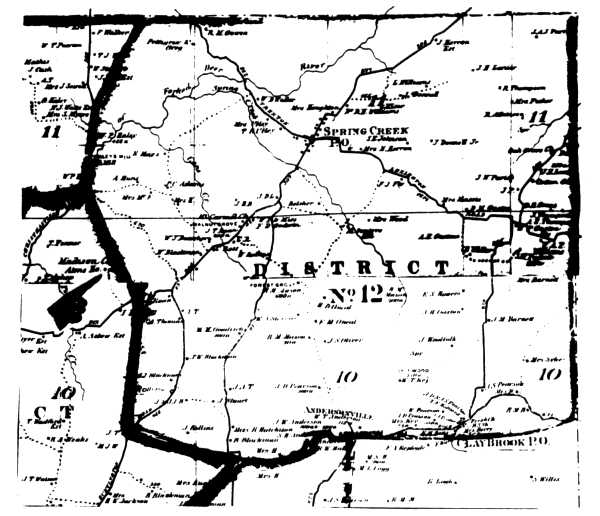

land, very well watered and timbered" located in Civil District 12, about eleven miles northeast of Jackson. (The dwellings and most of the farm were actually located in Civil District 11.) The county paid W. J. Seahorn $3600 for this property as an "asylum for the poor." Included was an acre and a half "used for a graveyard", which was "to be continued for that purpose", i.e. as a place of burial for paupers.[4] This burial ground had served the local community with burials dating back at least to the 1840s, of persons bearing the surnames of Goodrich, Cock and Fussell, among others. By present-day directions this farm was located near the village of Spring Creek and near the junction of Key Senter and George Anderson roads, principally on the south side of the former road.

|

|

|

D. G. Beers Map of Madison County, Tennessee, 1877, with a pointer |

James Adams was appointed superintendent of the poor asylum. The first persons admitted as inmates were received early in January 1871. Gradually the little settlement took shape: six small houses, each with a brick chimney, housed the inmates, segregated by race, black and white. A dwelling for the superintendent and stables, cribs and privies were built. Garden plots were laid out and fruit trees planted, from which the people on the "poor house farm" were fed. The manual work was done principally by hired laborers. By the time Adams left the job of supervising the institution, early in 1875, when inmates numbered twenty-three — about as many as ever occupied the farm at any given time — it was reported to the court that "the present system of caring for the poor for the last four years, we believe it to be a saving to the county" of six to eight thousand dollars annually.[5]

The magistrates were kept apprised of the business of the poor house farm by a commission or committee selected from among themselves; working with

(Page 27)

the superintendent they made recommendations for the farm's operation. Repairs were occasionally ordered; there was a regular turnover of superintendents, cooks and laborers. The county paid for the coffins of indigents who died on the farm and who were buried somewhat east of the older cemetery on the grounds.

Early in 1912 a suggestion was put to the magistrates that the poor house, the county work house and prison system be relocated, combining the location of these three institutions. It didn't meet with approval at that time.[6] Some of the isolation of the poor farm was relieved in 1911 when a telephone was installed there for use by the superintendent and inmates for business purposes rather than for strictly socializing.[7]

In April of 1916, the magistrates agreed to sell the poor farm, removing the inmates to the work house farm located almost four miles southwest of Jackson on what is now Westover Road.[8] The 257 acres, along with the 14 acre tract adjoining and a 20 acre tract acquired from the Blackmons and Cocks in 1881[9], comprising the poor house farm were sold in September 1916 to E. D. and N. F. Warlick for $5560, including the excluding the cemetery. (Although the old private cemetery and the indigents' cemetery were separated, the deed "lumped" them into one for the purpose of reserving the burial areas so that they would not be desecrated.)[10]

It was in July 1874 that the magistrates first considered the legality and practicality of establishing a work house where some criminals/convicts would be housed, persons who were sentenced to work on public projects, to defray the cost of maintenance of such individuals and to occupy prisoners in physical work. That fall the work house was set apart in the jail, under the management of the county sheriff.[11] The first task the work house inmates had was to repair the several levee roads south of Jackson at and over the south fork of the Forked Deer River; also engaged in the "cutting down" of Huntsman Hill on the Lexington road east of Jackson; in the latter these men provided the "muscle" for the job and neighborhood men provided the mules that pulled the scraper used to "plow down" this inconvenient obstruction to local traffic.[12]

In time the work house and jail were established on what is now Westover Road southwest of Jackson. To centralize these three county institutions the poor house was moved in 1916 to the county work house and penal farm. It was kept separate from the other two institutions, however, with distinct boundaries established between the indigents and the prisoners. Furthermore, the "paupers" were racially segregated in their new housing.[13] Once again the poor house land was planted in corn, vegetables and fruit towards the sustenance of the inmates of there. There were fewer in residence than in the "old days"; the periodic reports made to the county court suggest an average of a half-dozen whites and a half-dozen blacks, inmates, the numbers fluctuating with deaths and departures. It was even suggested in 1922 that the work house and poor house be consolidated but this suggestion was rejected.[14]

In order to maintain the legal residence of the poor house inmates, to avoid "dumping" of indigents from elsewhere at the expense of Madison County taxpayers, in July 1928 the magistrates determined that a person had to have been a resident of the county for at least six months before he or she applied for admittance to the poor house.[15] Any person with means of support had to make a small payment towards his/her sustenance or else f ace expulsion from the institution.[16] The work house, poor house farm was located south of the main east-west travelway from Jackson on what had been known for generations (and is yet called) the Lower Brownsville Road which was then and remains a winding road. In the summer of 1929 the magistrates approved the laying of an access road "north on and along said poor farm to the Lower Brownsville Road, connecting said highway with the Lower Brownsville Road by way of the poor farm."[17] This new connecting link

(Page 28)

created in 1930 is Moore Road, the main part of the poor house plant having been located at the southwest corner of Westover and Moore roads. A modernized county highway department was organized to maintain the local roads; part of the plant of the county highway department was established on the work house farm adjoining the poor house tract.

"Poor House" became ever more a noxious term, a subject of sad jokes and anyone living in such an institution was shamed, almost as a derelict, a pariah of society. To mitigate this slighting, the public began to refer to this old institution as the "county rest home," the term first appearing in a report to the county court early in 1938 [18]; gradually this became the name of the county home for indigents. With only a few residents at the rest home at this time, another move was set a-stir to abolish it, but benevolence prevailed and the move was rejected.[19] In 1941 major improvements were made at the rest home, i.e. plastering, papering and general repairs. There were fewer inmates as the Welfare Department had "found homes" for several of them.[20] Judging from the periodic reports made to the magistrates by the poor house committees a major and constant concern was that the inmates were well-fed, housed properly and allowed access to medical attention.

Early in 1945 the rest home committee was given authority over all the land south of U.S. Highway 70, known as the work house farm, with the exception of what had been designated for the county highway department. Over a year later a blueprint was ordered drawn of this property except for fifteen acres on which the prison and county highway garage were situated.[21] In 1948 several other parcels of land (about 42 acres and 2 lots) were sold of f the work house farm to private individuals.[22]

In time, a playground and recreation center was established on the old work house farm, a short distance south of the rest home itself. In September 1968 a committee was appointed to "investigate the present need for the county poor house or rest home." The committee found that there was "no longer any real need for one" and recommended that the rest home be closed by June 30, 1968. On November 20, 1967 the magistrates voted twenty-four to four in favor of this recommendation. The rest home was closed on January 1, 1968 and the equipment and supplies there were sold. The one remaining inmate was moved to another private institution.[23] The county retained the property although suggestions were made to sell it but finally late in 1977 it was turned over to the Madison County Highway Department.[24] In recent years a brick building was erected on this property, headquarters of the county highway department, facing Westover Road, directly across from the county prison and just north of the county recreation headquarters.

References

1. Madison County, Tennesee County Court Minute Book 10, page 259.

2. IBID., page 307. Book 11, pages 195, 408, 466, 508.

3. IBID. Book 11, page 514. October 4, 1870.

4. IBID. Book 12, page 14. Deed Book 29, page 261. Deed registered Nov. 10, 1871.

5. Madison County Court Minute Book 13, pages 414-415 (Jan. 5, 1875) and 486 (April 5, 1875). Also, WHIG-TRIBUNE, Jackson, Tenn., October 17, 1875.

6. Madison County Court Minute Book 27, pag8 110. January 1, 1912.

7. IBID. page 61. July 3, 1911.

8. IBID. Book 27, page 441. April 3, 1916.

9. Madison County Deed Book 29, page 4. May 2, 1881. Registered April 4, 1889.

10. IBID. Deed Book 88, page 191. Sept. 30, 1916; sale confirmed October 7, 1916.

11. Madison County Court Minute Book 12, page 231 (July 6, 1874) and page 320 (October 5, 1874).

12. IBID. page 356 (November 4, 1874) and page 409 (January 5, 1875).

13. IBID. Book 27, page 441. April 3, 1916.

(Page 29)

14. IBID. Book 32, page 215 (October 2, 1922) and page 286 (January 1, 1923).

15. IBID. page 479 (October 1, 1928) and page 546 (July 7, 1930).

16. A notable case was that of W. C. Hutchings whom the authorities learned had several hundred dollars in a local bank. The old man evidently needed institutionalized care and contributed to his "upkeep" and at his death he left the county $161.29. IBID. Book 37, page 207. October 7, 1935.

17. IBID. Book 32, page 509. July 1, 1929.

18. IBID. Book 37, page 367. January 3, 1928. "We only have eight inmates at the rest home now."

19. IBID. page 37. April 4, 1938.

20. IBID. Book 42, page 231. October 4, 1941. As early as 1938 social security payments from the federal government was enabling some persons from going to the "poor house." THE JACKSON SUN, April 4, 1938.

21. Madison County Court Minute Book 42, page 321 (Jan. 6, 1945) and page 461 (July 1, 1946).

22. IBID. Book 45, pages 233, 243. June 1, 1948.

23. IBID. Book C, pages 23; 318-319. September 18, 1967; page 321. January 15, 1968. The items sold brought $923.57. Book C, page 472. July 21, 1969.

24. IBID. Book D, page 45 (July 17, 1972); page 130 (July 16, 1973), page 565 (November 21, 1977).

U.S. Census, Madison County, Tennessee, June 4, 1880, page 8. Civil District 11.

Occupants of Poor House, managed by E. W. Goodrich:

Whites

Jasper Reams, age 25; Melissa Reams, age 35; William Walker, age 10; Dora Walker, age 7; Josie Reams, age 4; John Reams, age 2; Charlie Reams, born Oct. 1879; Nancy Weston, age 84; Emma Jewett, age 40; Sarah Weston, age 15; Susan Hodges, age 40; Louis Nichols, born Nov. 1879; John Britton, born March 1879; Fanny Britton, age 20.

Blacks

Phyllis Rollins, age 90; Eliza Mitchell, age 25; John Mitchell; Walter Montgomery, age 5; Osborne Sims, age 75; Eliza Meriwether, age 3; Rebecca Doris, age 84.

U.S. Census, Madison County, Tennessee, June 15, 1900, page 142. Civil District 11.

Occupants of Poor House, managed by John R. Tomlinson:

Whites

Tom Person, born May 1825, single; Fannie Rollins, born April 1820, single; Sallie Hudson, born Nov. 1835, single; Fannie Britton, born Jan. 1850, single; Jim Hutcherson, born Feb. 1823, single.

Blacks

Betty Taylor, born May 1830, single; Liza Mitchell, born Jan. 1851, single; Rachel Jackson, born May 1840, single; Jerry Howard, born April 1850, single; Sarah Taylor, born March 1875, single; Fanny Reid, born January 1896; Rosa Reid, born January 1897; Tom Cole, born May 1850, widower; Louis Taylor, born April 1884.

U.S. Census, Madison County, Tennessee, April 28, 1910, Enumeration District 164, Sheet 6-A.

Occupants of Poor House, managed by G. F. Haskins:

Whites

Philip Piolet, age 50, widowed; Jim Reed, age 47, single; Fannie Britton, age 55, single, Lizie Mitchell, age 65, widow.

Blacks

Henry White, age 50, widower; Ben Barnes, age 60, widower.

U.S. Census, Madison County, Tennessee, February 11, 1920, civil District 3.

Occupants of Poor House, managed by Carl Hunt:

Whites

Jeff Johnson, age 47, widowed; Dmetas Gillion, age 72, widowed; Rebecca Robertson, age 67, widowed; Essa Movell, female, age 52, single; Charlie Shelton, age 54, single; John F. Spark, age 59, widowed; Dan Irvin, age 72, widowed.

Blacks

Bill Jones, age 60, widowed; Alexander Hggy, age 80, widowed; Elizer Mitchell, female, age 80, widow; Lizzie Weary, age 60, widow; Fannie Raines, age 58, widow; Cos Smith, age 92, widowed; Lucinda Mitchell, age 95, widow; Roy Lyons, age 11; Willie D. Johnson, age 5; Loucile Johnson, age 1.

Return to Contents