OUR CLAYBROOK HERITAGE

(Madison County, Tennessee)

By Jonathan K. T. Smith

Copyright, Jonathan K. T. Smith, 1993.

EARLY SETTLEMENT

(Page 1)

In 1782 the North Carolina legislature set aside a military reservation in what is now upper Middle Tennessee, much of it in the Cumberland country. Land grants were made there for Revolutionary War veterans as compensation for their military services. When he served out his enlistment, a soldier was issued a certificate testifying to his service and an honorable discharge or he had to wait and make claim for his services years after the war. He could be rewarded with a grant of land in the western territories. The amount of acreage allotted was determined by military rank.

According to the Land Act of 1782, no claims could be entered before October 20, 1783. Within a few months, astute Eastern land speculators had sent out surveyors to lay off the best land for themselves, buying military warrants from veterans to convert into land claims. Getting land legally processed was tedious and expensive. An entry had to be made for the amount of land due the claimant and a survey with a plat drawn. It then was submitted to the secretary of state, who was authorized to issue a grant after it received the signature of the governor. The land office closed in Hillsboro, North Carolina in May of 1784, after operating for only seven months and after some four million acres of Tennessee land had been processed, principally by land speculators.

Even after North Carolina had ceded its western territory to the national government in 1790 the state retained its right to satisfy land grants for military service there. Then in 1796 when Tennessee was admitted into the Union, the two states agreed to work together in settling land claims. Although the Chickasaws had more or less agreed to relinquish their claim to land in Middle Tennessee, General James Robertson and Silas Dinsmoor signed a treaty of cession in July of 1805 with them for the east and north sections of the Congressional Reservation. In April of 1806 the United States agreed to turn over jurisdiction of all land grants to the State of Tennessee.

An important provision of the federal legislation of 1806 regarding the Congressional Reservation was that should there be insufficient land in that reservation then the lands south and west of it could be entered. This country became known as the WESTERN DISTRICT. The United States laid claim to all lands east of the Mississippi River based on the English Royal Charter of 1663 when the monarch then ruling laid theoretical claim to the eastern and transmontane lands in the south. However — in reality — the state and national governments treated with the various Indian tribes for this vast domain.

In 1806 Tennessee established two land off ices, one with headquarters in Knoxville for East Tennessee and one in Nashville for West (now Middle) Tennessee. Each office was supervised by a register who was qualified, by law to issue land grants. Complicating an already overloaded system, the state legislature established a Board of Commissioners for East and West Tennessee in 1807, whose members also could evaluate land claims and issue certificates for land grants. For years the two registers and the commissioners acted jointly to issue warrants or certificates for the state's public lands.

For an individual to acquire public land legally by gaining a title, he (or she) had first to secure a warrant or certificate from a land register or land commissioner for that specific acreage. Then one had to locate the land, have it entered upon an entry brook kept by an official entry-taker, who could record this entry so that it might then be laid out

(Page 2)

by an official land surveyor. This process completed, the claimant then submitted survey and plat to the secretary of state, who would attach a permanent number to the LAND GRANT. This was done to prevent duplications of numbers and over-lapping of some land claims.[1]

By 1838 North Carolinians had claimed some 8,500,000 acres out of approximately 24 million acres originally alloted to them in Middle and West Tennessee. For many years settlers had "squatted" on tracts of land, usually the less desirable tracts. These people generally were allowed to purchase their land on reasonable terms by what became known as "squatters' rights" or, more properly, occupant right claims.

Acting in the interest of the United States, the governments of North Carolina and Tennessee, Commissioners Andrew Jackson and Isaac Shelby made a treaty of cession with the Chickasaws for all their lands in West Tennessee and western Kentucky. Naturally, this followed the authorization by the United States Congress in April of 1818 for Tennessee rather than North Carolina to "issue grants and perfect titles to lands south and west of the Congressional Line in settlement of these claims." As explained previously, the whites theoretically claimed West Tennessee or the Western District but actually had to gain title to this region by means of purchase from the traditional Indian owners, the Chickasaws.

The Jackson Purchase was concluded on October 19, 1818 and ceded West Tennessee. The treaty of cession was accepted by the national government and ratified when it was signed by President James Monroe on January 7, 1819. The Tennessee legislature convened in October of that year and accepted the cession, expressed its intention to honor old North Carolina land grants and established land offices whereby these valuable lands could be distributed more effectively.[2]

On October 23, 1819 the state legislature divided the Western District into seven SURVEYORS' DISTRICTS. These then were divided into ranges that ran north and south in five-mile squares called sections. It was necessary for North Carolina grants to be cleared by October 1, 1820 to enable Tennessee purchasers and others holding occupant claims to make entry for their lands. On the first Wednesday of the December following, the general public was permitted to enter lands. Under the law, surveyors were allowed to receive entries for less than but not more than 160 acres. These modest land claims were the first of literally thousands that were made over the next eighty years. After January of 1825 the land dealings for the Western District were processed through the land office in Jackson.

|

|

|

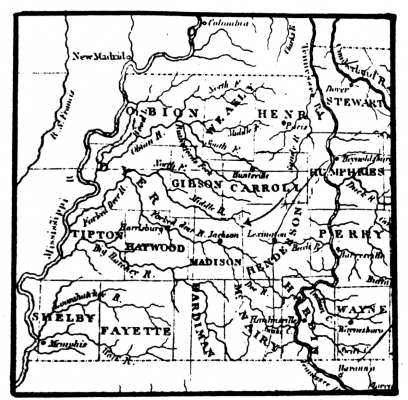

The WESTERN DISTRICT in the "Tennessee," a map by Anthony Finley, published in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1830. An arrow has been drawn in to show the general locality of northeast Madison County. |

(Page 3)

The Tennessee legislature in 1821 authorized that all the northeastern part of the Western District previously not specifically taken into an older county or created into a new one should be governed by Stewart County. A new county, MADISON, was created by legislative act on November 7, 1821. Its western and west-central areas lay in SURVEYOR'S DISTRICT 10. The mid-east and easternmost areas lay within SURVEYOR'S DISTRICT 9, with Samuel Wilson as Principal Surveyor in the latter district; his office was located in Lexington, Henderson County, Tennessee.

From 1820 until 1835, therefore, the more eastern section of Madison County and parts of other nearby counties, including Henderson County, were incorporated in Surveyor's District 9. In 1835, the surveyors' districts of the Western District were abolished, along with the system under which these districts were administered. The legislature then directed that all counties have their own entry-takers and surveyors, maintaining their records in their individual courthouses.

The records — maps, books, plats — of the 9th Surveyor's District were then deposited by legislative act, in the office of the entry-taker of Henderson County, Tennessee.[3] The Henderson County courthouse has burned twice in its history, in May of 1863 and July of 1895; each time most of the records of this county were destroyed. As a close survey of the land records of this county has been made, several times, by separate individuals and by the state in its public records microfilming project and as no records of the 9th Surveyor's District have surfaced (aside from a few maps and individual survey papers), it seems most likely that these records were either destroyed in May of 1863 and certainly if they had survived were destroyed in July of 1895.

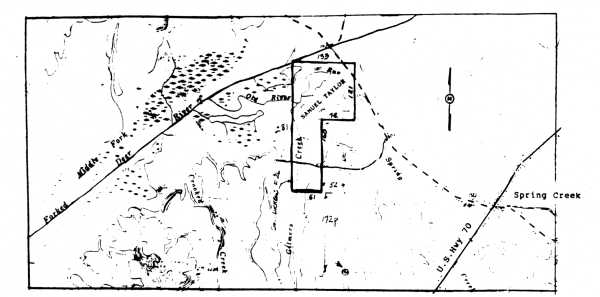

The CLAYBROOK vicinity lay within the 9th Surveyor's District, chiefly in Range 2, Sections 9 and 10. The civil districts created by the county court, in 1836, for this area in northeastern Madison County were given the numbers 12 and 13, the former the northernmost. Its principal settlement for many years was the village called SPRING CREEK, about four and a half miles — as the crow would fly — northwest of Claybrook.

Among the early settlers in this vicinity who petitioned the Tennessee legislature, for a new county to be created, a petition dated September 28, 1821, were John Hardgrove, James A. McLeary, Francis Taylor, Daniel Barcroft, Samuel Taylor, John Wear (Weir), George Wear (Weir) and Willis Chamberlin.[4]

The first area post off ice, known as the FORKED DEER PO, was effected, August 6, 1820, with Samuel Taylor as its first postmaster. It was ostensibly kept in Taylor's office in what later became Civil District 12, near present-day Spring Creek. He had acquired a 160 acre tract in Surveyor's District 9, Ranges 1-2, Section 11, as a land grant (#16934), April 13, 1822, having occupied it as a "squatter" for a good while before processing a full title for it.[5]

Taylor sold this tract to William May in March of 1823 and moved his office and his family into the new county seat, JACKSON.[6] On April 23, 1824 the post office was renamed, from Forked Deer PO to Jackson PO. He remained postmaster until his death, from lung disease, early in November of 1825.[7]

Replacing the Forked Deer PO in the community where it had actually been first located was the one called Spring Creek, effected in mid-April of 1824. SAMUEL DICKINS, one of the most influential land speculators in the Western District, lived on a large plantation, "Hazlewood" abutting Spring Creek and he served as the village postmaster, 1824-1832. The village that grew up around the Dickins settlements was the trading center for this

(Page 4)

|

|

|

Location of the Samuel Taylor 160 acre tract near Spring Creek, drawn from the deeds relating to this tract, by James H. Hanna, Civil Engineer (Ret.), Jackson, Tennessee. |

part of the county. It also became an educational center — with its own college. Families in the Claybrook vicinity traded with Spring Creek merchants before and after the Civil War and well into this century. COTTON GROVE in Civil District 13, with a post office from May of 1826, was also a village where area residents traded and attended religious and Masonic gatherings in the antebellum period.

Samuel Dickins (1781-1840), member of a prosperous, well-connected family, had served in the North Carolina House of Commons, 1813-1815; 1818; served briefly (December 2, 1816-March 3, 1817) in the U.S. House of Representatives. He and his wife, Jane (Vaughn) Dickins (a native of Mecklenburg County, Virginia) and their several children, moved from his native Person County, North Carolina, in 1820, to Madison County.

"He established himself as an efficient surveyor and locator of land in western Tennessee and in 1821 was appointed by Archibald D. Murphey and Joseph H. Bryan to locate and sell the Tennessee land claims of the University of North Carolina. His partner was Dr. Thomas Hunt; their firm, 'Hunt and Dickins,' employed numerous young men to help with the work. Dickins was compensated for his services with the usual 16 2/3 percent of the value of the lands surveyed. For selling, collecting and paying, he received 6 percent and later 10 percent, all payable in land. In an 1823 meeting of the university's board of trustees it was noted that he had sold 25, 000 acres of land, something over the amount specified. His actions were approved and commended and other sales were authorized from time to time."[8]

Samuel Dickins and his first wife, Jane, were buried on their plantation, "Hazlewood," but their remains and slab tombstones were moved to Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee early in this century.[9]

(Page 15)

REFERENCES

1. As detailed by one of the chief surveyors of the Western District, Memucan Hunt Howard. See, "Recollections of Memucan Hunt Howard," THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL MAGAZINE, volume 7, #1, January 1902, page 60.

2. Most of the land history background, furnished here, is from BENTON COUNTY, in the Tennessee County History series, Memphis State University Press, 1979, pages 16-22. Written by Jonathan K. T. Smith.

3. PUBLIC ACTS OF TENNESSEE, 1835-1836, Chapter 48, page 155.

4. Tennessee State Library and Archives (TSLA), Nashville: Legislative Petitions 61-1821.

5. Madison Co.: deed book 1, page 57, Samuel Taylor entered this 160 acre tract, officially, October 28, 1820; surveyed October 12, 1821; recorded in Madison County, February 12, 1823.

6. IBID.: deed book 1, page 307. Deed recorded June 20, 1825.

7. JACKSON GAZETTE, November 12, 1825.

8. DICTIONARY OF NORTH CAROLINA BIOGRAPHY, edited by William S. Powell, volume 2 (University of North Carolina Press, 1986), pages 64-65. "Samuel Dickins."

9. Jonathan Smith copied the date of birth (1781) and place of birth (Person Co., N.C.); date (1840) and place of death (Madison Co.) from

(Page 16)

the slab tombstone of Samuel Dickins and the birthplace (Mecklenburg Co., Va.) and death date (December 3, 1825) of Dickins' wife, Jane Vaughn, from her slab tombstone in Elmwood. Colonel Dickins married, secondly, Fanny Burton of Granville County, N.C., August 2, 1821. She survived him.

In his Jan. 14, 1839 LWT (proven Sept. 13, 1840), Colonel Dickins left his 2000 acre "Hazlewood" plantation to his widow as long as she chose to live upon it; then it was to be sold in the land division of his estate. The family graveyard was to bricked-in. He made several gifts to his would-be-soon widow and also among his several children, directing that his lands be divided among them in equal value tracts: Martha Dickins Bugg, Elizabeth Dickins Beloat; Thomas Dickins; Robert F. Dickins; Samuel B. Dickins; Edmund H. V. Dickins; Ann Dickins Martin; Sally Dickins Martin; and Mary Jane Dickins. (Madison Co.: will book 3, page 214)

Colonel Dickins' extensive lands were divided among his children, October 19, 1841 and September 25, 1843, including a lot and store upon it in Spring Creek to Mary Jane Dickins. (IBID., deed book 9, page 221; deed recorded on Feb. 3, 1844)

The Dickins heirs bought Fanny Dickins' interest in "Hazlewood" and agreed among themselves, with special financial adjustments, to sell the plantation to Martha L. Dickins and her husband, Dr. Joel Bugg, of Fayette Co., Tenn., January 22, 1841 (deed recorded April 26, 1841; deed book 7, page 435). The Buggs sold it to Dr. John C. Rogers (who had a partner, John L. Moore), for ten thousand dollars, January 31, 1846 (deed recorded June 8, 1846; deed book 10, page 428). The two partners mortgaged the place in June 1846 (IBID., page 436) but held on to this valuable real estate. Dr. Rogers bought 1110 acres of the 2000 acres from his partner, including the mill and mill pond, October 15, 1847 (deed recorded March 16, 1854; deed book 17, page 225).

Several of the Utley family bought 183 acres of Dr. Rogers' tract, including his homeplace, on the Lavinia Road, in 1866. (IBID., deed book 24, page 316) Dr. Rogers apparently was financially strapped as a trustee sold most of his Spring Creek properties at that time. On April 20, 1859 John L. Moore had sold a large portion of his share of these lands to J. P. and George W. Haughton, where Moore had lived formerly, for forty thousand dollars. It lay north of Spring Creek and on the south bank of the north fork of the Forked Deer River. Neighbors were Dr. Rogers on the west; Spring Creek on the south; J. P. Haughton, east and south; John Donnell, north and east; on the north by the south bank of the aforesaid river. (IBID., 23, page 343; deed recorded August 30, 1865)

Return to Contents