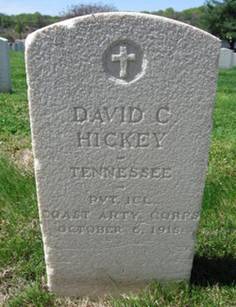

Pvt.

David Clifford Hickey

|

TWO GOLD STARS AT

ONCE FOR TOWN OF SWEETWATER SWEETWATER,

Tenn, Oct. 28--For the first time since the war

began Sweetwater soldiers are given in the casualty list. The blow falls harder, inasmuch as two

soldiers are numbered among the dead.

Willie Goad is dead of disease.

Young Goad's mother was a resident of this community at the time her

son enlisted. He enlisted early in the

war and had seen considerable service.

R.L. Hickey, who is a resident of Sweetwater, received a telegram

yesterday from the war department notifying him that his son, David C.

Hickey, was among those lost when the transport Otranto collided with the

steamer Kashmir off the Scottish coast early in the war and while still under

age, Mr. Hickey has two other sons in the service. Clifford Hickey

Buried in Mr.

R.L. Hickey, of this city, has just received word that the body of his son,

Clifford David, who lost his life in the sinking of the transport Otranto,

Oct. 6, 1918, off the Scottish coast, was recovered and buried along with a

number of his comrades in Mr.

Hickey had been unable to learn anything concerning the body of his son, until

a few days ago, when he was informed that it was picked up shortly after the

fatal accident. Young

Hickey was the first Sweetwater boy to make the supreme sacrifice, and was

only 19 years of age. The father has

not yet decided whether he will bring the body home, but states that he feels

that he should rest beside his comrades who died with him. Clifford Hickey

Body Returned Word

has been received by Mr. R.L. Hickey that the body of his son Clifford has

arrived in Clifford

Hickey will be remembered as the first Sweetwater boy to lose his life in the

late war, having been drowned when the transport Otranto was sunk of the

coast of Ben. F. Sands

Writes of Clifford Hickey’s Death Dear

Mr. Hickey and Family: Tonight,

the same as almost every night, my thoughts turn backward and I think of

home, my friends, and everything I left—gave up—in order to do what so many

American sons did, to help with the war. Now

that it is over, we feel proud of what we have accomplished. We want to get home and take up the

peaceful pursuits of happiness and contentment. In so doing there is going to be a little

feeling down deep in our hearts we will always try to cover, to hide. Why?

It is too sacred to speak, or write about. This is a longing for our comrades who went

away—and never returned. I

suppose you think that I have acted very out of the ordinary in not writing you

before about Clifford’s death. I never

knew anything about it until about six weeks ago, and it was such a shock I

was afraid to write then. To

write and speak of such occurrences is something that we seldom do over

here. Some things you can express as

well by mouth as by pen but the memory of a pal who has lot his life in this

war is far beyond that. How

shall I continue this letter? I can’t

realize that Clifford will not be there with his smile and word of cheer when

I return. He was so jolly and had some

good word every time I met him. Since

the last time I saw him, I have carried a secret that I have divulged to no

living being—the last word he said to me.

It was as he was getting on the train at God

knows, Mr. Hickey, it is hard enough for me to write this letter, so if I

make some of my sentences sound queer it is because I can’t find words to

express my feelings. After

you carry a heavy pack along a muddy road all night long and see your

comrades doing the same thing, almost ready to go to sleep while they

walk—and I have spoken to more than one unconscious man on his feet—you begin

to have a different feeling about friendship.

You never speak of it—just think, that’s all. My

only regret is that your boy—my friend—did not die while going over the top

instead of being caught in a trap, without a fighting chance. Your

golden star will shine in his memory, and its rays will be the light that

guides you in on to the source of all comfort. May

God comfort you and bless you in all your days, for the son you gave for your

country, is my prayer. Can’t

tell just when I am coming home, but hope to be there sometime in August. Feeling

fine, while attending the University at this place. Have no work to do at all. Write

when you can. Do hope you are all

well. Your

friend, Sgt.

Ben F. Sands, Toulouse University, Toulouse, France, Co. A, Bar. 1

HMS-Otranto September 25th saw the Otranto leaving Just after breakfast on Sunday morning 6 October 1918 there was a great jarring

and the ship trembled severely. The men on the Otranto were instructed

to remain calm and 15-20 minutes later were again instructed to get on deck

as quickly as possible. Once on deck the men were faced with very strong

winds. Strong enough that one had to hold on to something to keep from being

blown over. Soon the word was passed the another ship the Researcher and Designer |